What a Linux newbie needs to know: task management. How to run a program on Linux Running a process in the Linux background

Tasks and processes

Anything performed in Linux program called process. Linux as a multitasking system is characterized by the fact that many processes belonging to one or more users can be executed simultaneously. You can display a list of processes currently running using the command ps, for example, as follows:

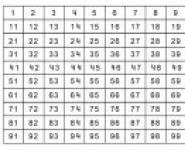

/home/larry# ps PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND 24 3 S 0:03 (bash) 161 3 R 0:00 ps /home/larry#

Please note that by default the command ps displays a list only of those processes that belong to the user who launched it. To view all processes running in the system, you need to issue the command ps -a . Process numbers(process ID, or PID), listed in the first column, are unique numbers that the system assigns to each running process. The last column, headed COMMAND, indicates the name of the command being run. In this case, the list contains processes launched by the user larry himself. There are many other processes running in the system, they full list can be viewed with the command ps-aux. However, among the commands run by user larry, there is only bash (the command shell for user larry) and the command itself ps. The bash shell can be seen running concurrently with the command ps. When the user entered the command ps, the bash shell started executing it. After the team ps has finished its work (the process table is displayed), control returns to the bash process. Then the bash shell displays a prompt and waits for a new command.

A running process is also called task(job). The terms process and task are used interchangeably. However, usually a process is called a task when it means job management(job control). Job control is a command shell feature that gives the user the ability to switch between multiple jobs.

In most cases, users will only run one task - this will be the last command they entered in the command shell. However, many shells (including bash and tcsh) have functions job management(job control), allowing you to run several commands at the same time or tasks(jobs) and, as needed, switch between them.

Job management can be useful if, for example, you are editing a large text file and want to temporarily interrupt editing to do some other operation. You can use the job management features to temporarily leave the editor, return to the shell prompt, and perform other actions. When they are done, you can return back to working with the editor and find it in the same state in which it was left. There are many more useful uses for job management functions.

Foreground and background mode

Tasks can be either foreground(foreground), or background(background). There can only be one task in the foreground at any given time. The foreground task is the task with which you are interacting; it receives input from the keyboard and sends output to the screen (unless, of course, you redirected the input or output somewhere else). Against, background jobs do not receive input from the terminal; Typically, such jobs do not require user interaction.

Some tasks take a very long time to complete, and nothing interesting happens while they are running. An example of such tasks is compiling programs, as well as compressing large files. There's no reason to stare at the screen and wait for these tasks to complete. Such jobs should be run in the background. During this time, you can work with other programs.

To control the execution of processes in Linux, a transfer mechanism is provided signals. A signal is the ability of processes to exchange standard short messages directly using the system. The signal message does not contain any information except the signal number (for convenience, a name predefined by the system can be used instead of a number). In order to transmit a signal, the process only needs to use system call kill(), and in order to receive the signal, you don’t need anything. If a process needs to respond to a signal in some special way, it can register handler, and if there is no handler, the system will react for it. Typically, this causes the process that received the signal to terminate immediately. The signal handler starts asynchronously, immediately upon receiving the signal, no matter what the process is doing at the time.

Two signals - number 9 ( KILL) and 19 ( STOP) - always processed by the system. The first of them is needed in order to kill the process for sure (hence the name). Signal STOP suspends process: in this state, the process is not removed from the process table, but is not executed until it receives signal 18 ( CONT) - after which it will continue to work. In the Linux command shell, the signal STOP can be passed to the active process using an escape sequence Ctrl -Z .

Signal number 15 ( TERM) serves to interrupt the job. At interruption(interrupt) job process dies. Jobs are usually interrupted by an escape sequence Ctrl -C. There is no way to restore an interrupted job. You should also be aware that some programs intercept the signal TERM(using a handler), so that pressing a key combination Ctrl -C(o) may not abort the process immediately. This is done so that the program can destroy traces of its work before it is completed. In practice, some programs cannot be interrupted in this way at all.

Transferring to background and destroying jobs

Let's start with simple example. Let's look at the yes command, which at first glance may seem useless. This command sends an endless stream of strings consisting of the character y to standard output. Let's see how this command works:

/home/larry# yes y y y y y

The sequence of such lines will continue indefinitely. You can destroy this process by sending it an interrupt signal, i.e. by pressing Ctrl -C. Let's do things differently now. To prevent this endless sequence from being displayed on the screen, we will redirect the standard output of the yes command to /dev/null . As you may know, the /dev/null device acts as a "black hole": all data sent to this device is lost. Using this device it is very convenient to get rid of too much output from some programs.

/home/larry# yes > /dev/null

Now nothing is displayed on the screen. However, the shell prompt is also not returned. This is because the yes command is still running and sending its messages consisting of the letters y to /dev/null . You can also destroy this task by sending it an interrupt signal.

Now let's say you want the yes command to continue to work, but also to return the shell prompt to the screen so that you can work with other programs. To do this, you can put the yes command into the background, and it will work there without communicating with you.

One way to put a process into the background is to append an & to the end of the command. Example:

/home/larry# yes > /dev/null & + 164 /home/larry#

The message is job number(job number) for the process yes. The command shell assigns a job number to each job it runs. Since yes is the only executable job, it is assigned the number 1. The number 164 is the identification number associated with this process (PID), and this number is also given to the process by the system. As we will see later, a process can be accessed by specifying both of these numbers.

So now we have a yes process running in the background, continuously sending a stream of y's to the /dev/null device. In order to find out the status of this process, you need to execute the command jobs, which is a shell internal command.

/home/larry# jobs + Running yes >/dev/null & /home/larry#

We see that this program really works. In order to find out the status of a task, you can also use the command ps, as shown above.

In order to transmit a signal to the process (most often there is a need interrupt job job) the utility is used kill. This command is given either a job number or a PID as an argument. An optional parameter is the number of the signal that needs to be sent to the process. By default the signal is sent TERM. In the above case, the job number was 1, so the command kill %1 will interrupt the job. When a job is accessed by its number (rather than its PID), then that number must be preceded by a percent symbol (“%”) on the command line.

Now let's enter the command jobs again to check the result of the previous action:

/home/larry# jobs Terminated yes >/dev/null

In fact, the job is destroyed, and the next time you enter the jobs command, there will be no information about it on the screen.

You can also kill a job using the process identification number (PID). This number, along with the job identification number, is indicated when the job starts. In our example, the PID value was 164, so the command kill 164 would be equivalent to the command kill %1. When using PID as an argument to the kill command, you do not need to enter the "%" character.

Pausing and resuming jobs

Let's first start the process with the yes command in the foreground, as was done before:

/home/larry# yes > /dev/null

As before, because the process is running in the foreground, the shell prompt does not return to the screen.

Now, instead of interrupting the task with a key combination Ctrl -C, the task is possible suspend(suspend, literally - to suspend), sending him a signal STOP. To pause a task, you need to press the appropriate key combination, usually this Ctrl -Z .

/home/larry# yes > /dev/null Ctrl -Z+ Stopped yes >/dev/null /home/larry#

The suspended process simply does not execute. It does not consume processor resources. A suspended task can be started to run from the same point as if it had not been suspended.

To resume the job running in the foreground, you can use the command fg(from the word foreground - foreground).

/home/larry# fg yes >/dev/null

The command shell will once again display the command name so that the user knows which task he is in. this moment launched in the foreground. Let's pause this task again by pressing the keys Ctrl -Z, but this time let's launch it into the background with the command bg(from the word background - background). This will cause the process to run as if it had been run using a command with an & at the end (as was done in the previous section):

/home/larry# bg + yes $>$/dev/null & /home/larry#

The shell prompt is returned. Now the team jobs must show that the process yes is actually working at the moment; this process can be killed with the command kill, as it was done before.

You cannot use the keyboard shortcut to pause a task running in the background Ctrl -Z. Before pausing a job, it must be brought to the foreground with the command fg and only then stop. Thus, the command fg can be applied to either suspended jobs or to a job running in the background.

There is a big difference between background jobs and suspended jobs. A suspended task does not work - no money is spent on it computing power processor. This job does not perform any action. A suspended task occupies a certain amount of computer RAM; after some time, the kernel will pump out this part of the memory to HDD « poste restante" In contrast, a background job is running, using memory, and doing some things you might want to do, but you may be working on other programs at the same time.

Jobs running in the background may attempt to display some text on the screen. This will interfere with working on other tasks.

/home/larry# yes &

Here the standard output has not been redirected to the /dev/null device, so an endless stream of y characters will be printed to the screen. This thread cannot be stopped because the key combination Ctrl -C does not affect jobs in the background. In order to stop this output, you need to use the command fg, which will bring the task to the foreground, and then destroy the task with a key combination Ctrl -C .

Let's make one more remark. Usually by team fg and the team bg affect those jobs that were most recently suspended (these jobs will be marked with a + symbol next to the job number if you enter the command jobs). If one or more jobs are running at the same time, jobs can be placed in the foreground or background by specifying commands as arguments fg or commands bg their identification number (job ID). For example, the command fg %2 puts job number 2 to the front and the command bg %3 puts job number 3 in the background. Use PIDs as command arguments fg And bg it is forbidden.

Moreover, to bring a job to the foreground, you can simply specify its number. Yes, team %2 will be equivalent to the command fg %2 .

It is important to remember that the job control function belongs to the shell. Teams fg , bg And jobs are shell internal commands. If, for some reason, you are using a command shell that does not support job management functions, then you will not find these (and similar) commands in it.

Starting and processing background processes: job management

You may have noticed that after you entered the command into Terminal "e, you usually need to wait for it to complete before shell will give you back control. This means that you ran the command inpriority mode . However, there are times when this is not desirable.

Let's say, for example, that you decide to recursively copy one large directory to another. You also chose to ignore errors, so you redirected the error channel to/dev/null :

| cp -R images/ /shared/ 2>/dev/null |

This command may take several minutes to complete. You have two solutions: the first is cruel, implying stopping (killing) the command, and then executing it again, but at a more appropriate time. To do this, click Ctrl+c : This will end the process and take you back to the prompt. But wait, don't do that just yet! Read on.

Let's say you want a command to execute while you do something else. The solution would be to run the process inbackground . To do this, click Ctrl+z to pause the process:

In this case, the process will continue its work, but as a background task, as indicated by the sign & (ampersand) at the end of the line. You will then be taken back to the prompt and can continue working. A process that runs as a background task, or in the background, is called backgroundtask .

Of course, you can immediately run processes as background tasks by adding the sign & at the end of the command. For example, you can run the directory copy command in the background by typing:

| cp -R images/ /shared/ 2>/dev/null & |

If you want, you can also restore this process to foreground and wait for it to complete by typingfg (ForeGround - priority). To put it back into the background, enter the following sequence Ctrl+z , bg .

In this way, you can run several tasks: each command will be assigned a task number. Team shell "a jobs

displays a list of all jobs associated with the current one shell "om. Before the task there is a sign +

, marking the last process running in the background. To restore a specific job to priority mode, you can enter the commandfg

Last time we talked about working with input, output, and error streams in bash scripts, file descriptors, and stream redirection. Now you already know enough to write something of your own. At this stage of mastering bash, you may well have questions about how to manage running scripts and how to automate their launch.

So far we've been typing script names into the command line and hitting Enter, which causes the programs to run immediately, but this isn't the case. the only way calling scripts. Today we will talk about how a script can work with Linux signals, about different approaches to running scripts and managing them while running.

Linux Signals

In Linux, there are more than three dozen signals that are generated by the system or applications. Here is a list of the most commonly used ones, which will certainly come in handy when developing scripts command line.| Signal code |

Name |

Description |

| 1 |

SIGHUP |

Closing the terminal |

| 2 |

SIGINT |

Signal to stop the process by the user from the terminal (CTRL + C) |

| 3 |

SIGQUIT |

Signal to stop a process by the user from the terminal (CTRL + \) with a memory dump |

| 9 |

SIGKILL |

Unconditional termination of the process |

| 15 |

SIGTERM |

Process termination request signal |

| 17 |

SIGSTOP |

Forcing a process to be suspended but not terminated |

| 18 |

SIGTSTP |

Pausing a process from the terminal (CTRL+Z) but not shutting down |

| 19 |

SIGCONT |

Continue execution of a previously stopped process |

If the bash shell receives a SIGHUP signal when you close the terminal, it exits. Before exiting, it sends a SIGHUP signal to all processes running in it, including running scripts.

The SIGINT signal causes operation to temporarily stop. The Linux kernel stops allocating processor time to the shell. When this happens, the shell notifies processes by sending them a SIGINT signal.

Bash scripts do not control these signals, but they can recognize them and execute certain commands to prepare the script for the consequences caused by the signals.

Sending signals to scripts

The bash shell allows you to send signals to scripts using keyboard shortcuts. This comes in very handy if you need to temporarily stop a running script or terminate its operation.Terminating a process

Combination CTRL keys+C generates the SIGINT signal and sends it to all processes running in the shell, causing them to terminate.Let's run the following command in the shell:

$sleep 100

After that, we will complete its work with the key combination CTRL + C.

Terminate a process from the keyboard

Temporarily stopping the process

The CTRL + Z key combination generates the SIGTSTP signal, which suspends the process but does not terminate it. Such a process remains in memory and its work can be resumed. Let's run the command in the shell:$sleep 100

And temporarily stop it with the key combination CTRL + Z.

Pause the process

The number in square brackets is the job number that the shell assigns to the process. The shell treats processes running within it as jobs with unique numbers. The first process is assigned number 1, the second - 2, and so on.

If you pause a job bound to a shell and try to exit it, bash will issue a warning.

You can view suspended jobs with the following command:

Ps –l

Task list

In the S column, which displays the process status, T is displayed for suspended processes. This indicates that the command is either suspended or in a trace state.

If you need to terminate a suspended process, you can use the kill command. You can read details about it.

Her call looks like this:

Kill processID

Signal interception

To enable Linux signal tracking in a script, use the trap command. If the script receives the signal specified when calling this command, it processes it independently, while the shell will not process such a signal.The trap command allows the script to respond to signals such as otherwise their processing is performed by the shell without his participation.

Let's look at an example that shows how the trap command specifies the code to be executed and a list of signals, separated by spaces, that we want to intercept. In this case it is just one signal:

#!/bin/bash trap "echo " Trapped Ctrl-C"" SIGINT echo This is a test script count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($ count + 1)) done

The trap command used in this example outputs text message whenever it detects a SIGINT signal, which can be generated by pressing Ctrl + C on the keyboard.

Signal interception

Every time you press CTRL + C , the script executes the echo command specified when calling trace instead of letting the shell terminate it.

You can intercept the script exit signal by using the name of the EXIT signal when calling the trap command:#!/bin/bash trap "echo Goodbye..." EXIT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Intercepting the script exit signal

When the script exits, either normally or due to a SIGINT signal, the shell will intercept and execute the echo command.

Modification of intercepted signals and cancellation of interception

To modify signals intercepted by the script, you can run the trap command with new parameters:#!/bin/bash trap "echo "Ctrl-C is trapped."" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1) ) done trap "echo "I modified the trap!"" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Second Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Signal interception modification

After modification, the signals will be processed in a new way.

Signal interception can also be canceled by simply executing the trap command, passing it a double dash and the signal name:

#!/bin/bash trap "echo "Ctrl-C is trapped."" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1) ) done trap -- SIGINT echo "I just removed the trap" count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Second Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

If the script receives a signal before the trap is canceled, it will process it as specified in the current trap command. Let's run the script:

$ ./myscript

And press CTRL + C on the keyboard.

Signal intercepted before interception was cancelled.

The first press of CTRL + C occurred at the time of script execution, when signal interception was in effect, so the script executed the echo command assigned to the signal. After execution reached the unhook command, the CTRL + C command worked as usual, terminating the script.

Running command line scripts in the background

Sometimes bash scripts take a long time to complete a task. However, you may need to be able to work normally on the command line without waiting for the script to complete. It's not that difficult to implement.If you've seen the list of processes output by the ps command, you may have noticed processes that are running in the background and not tied to a terminal.

Let's write the following script:

#!/bin/bash count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Let's run it by specifying the ampersand character (&) after the name:

$ ./myscipt &

This will cause it to run as a background process.

Running a script in the background

The script will be launched in a background process, its identifier will be displayed in the terminal, and when its execution is completed, you will see a message about this.

Note that although the script runs in the background, it continues to use the terminal to output messages to STDOUT and STDERR, meaning that the text it outputs or error messages will be visible in the terminal.

List of processes

With this approach, if you exit the terminal, the script running in the background will also exit.

What if you want the script to continue running after closing the terminal?

Executing scripts that do not exit when closing the terminal

Scripts can be executed in background processes even after exiting the terminal session. To do this, you can use the nohup command. This command allows you to run a program by blocking SIGHUP signals sent to the process. As a result, the process will be executed even when you exit the terminal in which it was launched.Let's apply this technique when running our script:

Nohup ./myscript &

This is what will be output to the terminal.

Team nohup

The nohup command untethers a process from the terminal. This means that the process will lose references to STDOUT and STDERR. In order not to lose the data output by the script, nohup automatically redirects messages arriving in STDOUT and STDERR to the nohup.out file.

Note that if you run multiple scripts from the same directory, their output will end up in a single nohup.out file.

View assignments

The jobs command allows you to view current jobs that are running in the shell. Let's write the following script:#!/bin/bash count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 10 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Let's run it:

$ ./myscript

And temporarily stop it with the key combination CTRL + Z.

Running and pausing a script

Let's run the same script in the background, while redirecting the script's output to a file so that it does not display anything on the screen:

$ ./myscript > outfile &

By now executing the jobs command, we will see information about both the suspended script and the one running in the background.

Getting information about scripts

The -l switch when calling the jobs command indicates that we need information about process IDs.

Restarting suspended jobs

To restart the script in the background, you can use the bg command.Let's run the script:

$ ./myscript

Press CTRL + Z, which will temporarily stop its execution. Let's run the following command:

$bg

bg command

The script is now running in the background.

If you have multiple suspended jobs, you can pass the job number to the bg command to restart a specific job.

To restart the job normally, use the fg command:

Planning to run scripts

Linux provides a couple of ways to run bash scripts in specified time. These are the at command and the cron job scheduler.The at command looks like this:

At [-f filename] time

This command recognizes many time formats.

- Standard, indicating hours and minutes, for example - 10:15.

- Using AM/PM indicators, before or after noon, for example - 10:15PM.

- Using special names such as now , noon , midnight .

- A standard date format in which the date is written using the patterns MMDDYY, MM/DD/YY, or DD.MM.YY.

- A text representation of the date, for example, Jul 4 or Dec 25, while the year can be specified, or you can do without it.

- Recording like now + 25 minutes .

- Recording view 10:15PM tomorrow .

- Recording type 10:15 + 7 days.

$ at -f ./myscript now

Scheduling jobs using the at command

The -M switch when calling at is used to send what the script outputs to e-mail, if the system is configured accordingly. If sending email is not possible, this switch will simply suppress the output.

To view the list of jobs waiting to be executed, you can use the atq command:

List of pending tasks

Deleting pending jobs

The atrm command allows you to delete a pending job. When calling it, indicate the task number:$atrm 18

Deleting a job

Run scripts on a schedule

Scheduling your scripts to run once using the at command can make life easier in many situations. But what if you need the script to be executed at the same time every day, or once a week, or once a month?Linux has a crontab utility that allows you to schedule scripts that need to be run regularly.

Crontab runs in the background and, based on data in so-called cron tables, runs scheduled jobs.

To view an existing cron job table, use the following command:

$ crontab –l

When scheduling a script to run on a schedule, crontab accepts data about when the job needs to be executed in the following format:

Minute, hour, day of the month, month, day of the week.

For example, if you want a certain script named command to be executed every day at 10:30, this will correspond to the following entry in the task table:

30 10 * * * command

Here, the wildcard "*" used for the day of month, month, and day of week fields indicates that cron should run the command every day of every month at 10:30 AM.

If, for example, you want the script to run at 4:30 PM every Monday, you will need to create the following entry in the tasks table:

30 16 * * 1 command

The numbering of the days of the week starts from 0, 0 means Sunday, 6 means Saturday. Here's another example. Here the command will be executed at 12 noon on the first day of every month.

00 12 1 * * command

Months are numbered starting from 1.

In order to add an entry to a table, you need to call crontab with the -e switch:

Crontab –e

Then you can enter schedule generation commands:

30 10 * * * /home/likegeeks/Desktop/myscript

Thanks to this command, the script will be called every day at 10:30. If you encounter the "Resource temporarily unavailable" error, run the command below as root:

$ rm -f /var/run/crond.pid

You can organize periodic launch of scripts using cron even easier by using several special directories:

/etc/cron.hourly /etc/cron.daily /etc/cron.weekly /etc/cron.monthly

Placing a script file in one of them will cause it to run hourly, daily, weekly or monthly, respectively.

Run scripts on login and shell startup

You can automate the launch of scripts based on various events, such as user login or shell launch. You can read about files that are processed in such situations. For example, these are the following files:$HOME/.bash_profile $HOME/.bash_login $HOME/.profile

To run a script on login, place its call in the .bash_profile file.

What about running scripts when you open a terminal? The .bashrc file will help you organize this.

Results

Today we discussed issues related to management life cycle scripts, we talked about how to run scripts in the background, how to schedule their execution. Next time, read about functions in bash scripts and library development.Dear readers! Do you use tools to schedule command line scripts to run on a schedule? If yes, please tell us about them.

Last time we talked about working with input, output, and error streams in bash scripts, file descriptors, and stream redirection. Now you already know enough to write something of your own. At this stage of mastering bash, you may well have questions about how to manage running scripts and how to automate their launch.

So far, we've typed script names into the command line and pressed Enter, which caused the programs to run immediately, but that's not the only way to call scripts. Today we will talk about how a script can work with Linux signals, about different approaches to running scripts and managing them while running.

Linux Signals

In Linux, there are more than three dozen signals that are generated by the system or applications. Here is a list of the most commonly used ones that will surely come in handy when developing command line scripts.| Signal code |

Name |

Description |

| 1 |

SIGHUP |

Closing the terminal |

| 2 |

SIGINT |

Signal to stop the process by the user from the terminal (CTRL + C) |

| 3 |

SIGQUIT |

Signal to stop a process by the user from the terminal (CTRL + \) with a memory dump |

| 9 |

SIGKILL |

Unconditional termination of the process |

| 15 |

SIGTERM |

Process termination request signal |

| 17 |

SIGSTOP |

Forcing a process to be suspended but not terminated |

| 18 |

SIGTSTP |

Pausing a process from the terminal (CTRL+Z) but not shutting down |

| 19 |

SIGCONT |

Continue execution of a previously stopped process |

If the bash shell receives a SIGHUP signal when you close the terminal, it exits. Before exiting, it sends a SIGHUP signal to all processes running in it, including running scripts.

The SIGINT signal causes operation to temporarily stop. The Linux kernel stops allocating processor time to the shell. When this happens, the shell notifies processes by sending them a SIGINT signal.

Bash scripts do not control these signals, but they can recognize them and execute certain commands to prepare the script for the consequences caused by the signals.

Sending signals to scripts

The bash shell allows you to send signals to scripts using keyboard shortcuts. This comes in very handy if you need to temporarily stop a running script or terminate its operation.Terminating a process

The CTRL + C key combination generates a SIGINT signal and sends it to all processes running in the shell, causing them to terminate.Let's run the following command in the shell:

$sleep 100

After that, we will complete its work with the key combination CTRL + C.

Terminate a process from the keyboard

Temporarily stopping the process

The CTRL + Z key combination generates the SIGTSTP signal, which suspends the process but does not terminate it. Such a process remains in memory and its work can be resumed. Let's run the command in the shell:$sleep 100

And temporarily stop it with the key combination CTRL + Z.

Pause the process

The number in square brackets is the job number that the shell assigns to the process. The shell treats processes running within it as jobs with unique numbers. The first process is assigned number 1, the second - 2, and so on.

If you pause a job bound to a shell and try to exit it, bash will issue a warning.

You can view suspended jobs with the following command:

Ps –l

Task list

In the S column, which displays the process status, T is displayed for suspended processes. This indicates that the command is either suspended or in a trace state.

If you need to terminate a suspended process, you can use the kill command. You can read details about it.

Her call looks like this:

Kill processID

Signal interception

To enable Linux signal tracking in a script, use the trap command. If the script receives the signal specified when calling this command, it processes it independently, while the shell will not process such a signal.The trap command allows the script to respond to signals that would otherwise be processed by the shell without its intervention.

Let's look at an example that shows how the trap command specifies the code to be executed and a list of signals, separated by spaces, that we want to intercept. In this case it is just one signal:

#!/bin/bash trap "echo " Trapped Ctrl-C"" SIGINT echo This is a test script count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($ count + 1)) done

The trap command used in this example prints a text message whenever it encounters a SIGINT signal, which can be generated by pressing Ctrl + C on the keyboard.

Signal interception

Every time you press CTRL + C , the script executes the echo command specified when calling trace instead of letting the shell terminate it.

You can intercept the script exit signal by using the name of the EXIT signal when calling the trap command:#!/bin/bash trap "echo Goodbye..." EXIT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Intercepting the script exit signal

When the script exits, either normally or due to a SIGINT signal, the shell will intercept and execute the echo command.

Modification of intercepted signals and cancellation of interception

To modify signals intercepted by the script, you can run the trap command with new parameters:#!/bin/bash trap "echo "Ctrl-C is trapped."" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1) ) done trap "echo "I modified the trap!"" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Second Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Signal interception modification

After modification, the signals will be processed in a new way.

Signal interception can also be canceled by simply executing the trap command, passing it a double dash and the signal name:

#!/bin/bash trap "echo "Ctrl-C is trapped."" SIGINT count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1) ) done trap -- SIGINT echo "I just removed the trap" count=1 while [ $count -le 5 ] do echo "Second Loop #$count" sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

If the script receives a signal before the trap is canceled, it will process it as specified in the current trap command. Let's run the script:

$ ./myscript

And press CTRL + C on the keyboard.

Signal intercepted before interception was cancelled.

The first press of CTRL + C occurred at the time of script execution, when signal interception was in effect, so the script executed the echo command assigned to the signal. After execution reached the unhook command, the CTRL + C command worked as usual, terminating the script.

Running command line scripts in the background

Sometimes bash scripts take a long time to complete a task. However, you may need to be able to work normally on the command line without waiting for the script to complete. It's not that difficult to implement.If you've seen the list of processes output by the ps command, you may have noticed processes that are running in the background and not tied to a terminal.

Let's write the following script:

#!/bin/bash count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do sleep 1 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Let's run it by specifying the ampersand character (&) after the name:

$ ./myscipt &

This will cause it to run as a background process.

Running a script in the background

The script will be launched in a background process, its identifier will be displayed in the terminal, and when its execution is completed, you will see a message about this.

Note that although the script runs in the background, it continues to use the terminal to output messages to STDOUT and STDERR, meaning that the text it outputs or error messages will be visible in the terminal.

List of processes

With this approach, if you exit the terminal, the script running in the background will also exit.

What if you want the script to continue running after closing the terminal?

Executing scripts that do not exit when closing the terminal

Scripts can be executed in background processes even after exiting the terminal session. To do this, you can use the nohup command. This command allows you to run a program by blocking SIGHUP signals sent to the process. As a result, the process will be executed even when you exit the terminal in which it was launched.Let's apply this technique when running our script:

Nohup ./myscript &

This is what will be output to the terminal.

Team nohup

The nohup command untethers a process from the terminal. This means that the process will lose references to STDOUT and STDERR. In order not to lose the data output by the script, nohup automatically redirects messages arriving in STDOUT and STDERR to the nohup.out file.

Note that if you run multiple scripts from the same directory, their output will end up in a single nohup.out file.

View assignments

The jobs command allows you to view current jobs that are running in the shell. Let's write the following script:#!/bin/bash count=1 while [ $count -le 10 ] do echo "Loop #$count" sleep 10 count=$(($count + 1)) done

Let's run it:

$ ./myscript

And temporarily stop it with the key combination CTRL + Z.

Running and pausing a script

Let's run the same script in the background, while redirecting the script's output to a file so that it does not display anything on the screen:

$ ./myscript > outfile &

By now executing the jobs command, we will see information about both the suspended script and the one running in the background.

Getting information about scripts

The -l switch when calling the jobs command indicates that we need information about process IDs.

Restarting suspended jobs

To restart the script in the background, you can use the bg command.Let's run the script:

$ ./myscript

Press CTRL + Z, which will temporarily stop its execution. Let's run the following command:

$bg

bg command

The script is now running in the background.

If you have multiple suspended jobs, you can pass the job number to the bg command to restart a specific job.

To restart the job normally, use the fg command:

Planning to run scripts

Linux provides a couple of ways to run bash scripts at a given time. These are the at command and the cron job scheduler.The at command looks like this:

At [-f filename] time

This command recognizes many time formats.

- Standard, indicating hours and minutes, for example - 10:15.

- Using AM/PM indicators, before or after noon, for example - 10:15PM.

- Using special names such as now , noon , midnight .

- A standard date format in which the date is written using the patterns MMDDYY, MM/DD/YY, or DD.MM.YY.

- A text representation of the date, for example, Jul 4 or Dec 25, while the year can be specified, or you can do without it.

- Recording like now + 25 minutes .

- Recording view 10:15PM tomorrow .

- Recording type 10:15 + 7 days.

$ at -f ./myscript now

Scheduling jobs using the at command

The -M switch when calling at is used to send what the script outputs by email if the system is configured to do so. If sending an email is not possible, this key will simply suppress the output.

To view the list of jobs waiting to be executed, you can use the atq command:

List of pending tasks

Deleting pending jobs

The atrm command allows you to delete a pending job. When calling it, indicate the task number:$atrm 18

Deleting a job

Run scripts on a schedule

Scheduling your scripts to run once using the at command can make life easier in many situations. But what if you need the script to be executed at the same time every day, or once a week, or once a month?Linux has a crontab utility that allows you to schedule scripts that need to be run regularly.

Crontab runs in the background and, based on data in so-called cron tables, runs scheduled jobs.

To view an existing cron job table, use the following command:

$ crontab –l

When scheduling a script to run on a schedule, crontab accepts data about when the job needs to be executed in the following format:

Minute, hour, day of the month, month, day of the week.

For example, if you want a certain script named command to be executed every day at 10:30, this will correspond to the following entry in the task table:

30 10 * * * command

Here, the wildcard "*" used for the day of month, month, and day of week fields indicates that cron should run the command every day of every month at 10:30 AM.

If, for example, you want the script to run at 4:30 PM every Monday, you will need to create the following entry in the tasks table:

30 16 * * 1 command

The numbering of the days of the week starts from 0, 0 means Sunday, 6 means Saturday. Here's another example. Here the command will be executed at 12 noon on the first day of every month.

00 12 1 * * command

Months are numbered starting from 1.

In order to add an entry to a table, you need to call crontab with the -e switch:

Crontab –e

Then you can enter schedule generation commands:

30 10 * * * /home/likegeeks/Desktop/myscript

Thanks to this command, the script will be called every day at 10:30. If you encounter the "Resource temporarily unavailable" error, run the command below as root:

$ rm -f /var/run/crond.pid

You can organize periodic launch of scripts using cron even easier by using several special directories:

/etc/cron.hourly /etc/cron.daily /etc/cron.weekly /etc/cron.monthly

Placing a script file in one of them will cause it to run hourly, daily, weekly or monthly, respectively.

Run scripts on login and shell startup

You can automate the launch of scripts based on various events, such as user login or shell launch. You can read about files that are processed in such situations. For example, these are the following files:$HOME/.bash_profile $HOME/.bash_login $HOME/.profile

To run a script on login, place its call in the .bash_profile file.

What about running scripts when you open a terminal? The .bashrc file will help you organize this.

Results

Today we looked at issues related to script lifecycle management, talked about how to run scripts in the background, how to schedule their execution. Next time, read about functions in bash scripts and library development.Dear readers! Do you use tools to schedule command line scripts to run on a schedule? If yes, please tell us about them.